“I want to teach you something that I bet nobody in your house knows.”

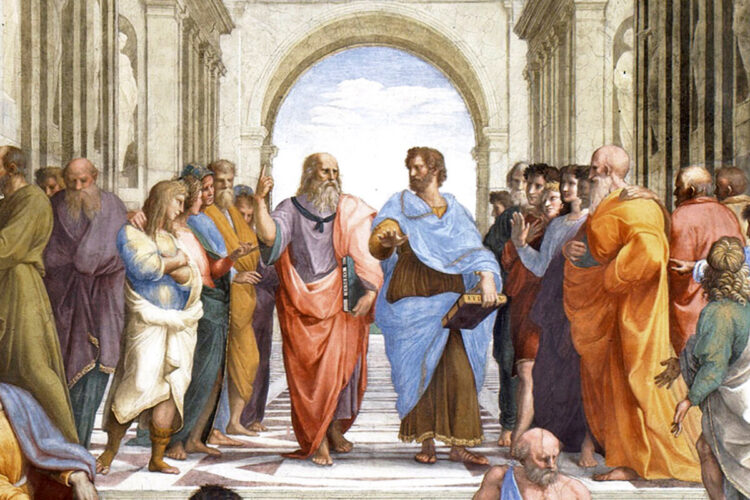

Diana Smith stands at the head of a cluttered classroom at Washington Latin Public Charter School. The lights are dimmed, and projected on the wall behind is one of the most famous images in European art, Raphael’s The School of Athens, which acts as the anchor for today’s lesson in art, history and philosophy.

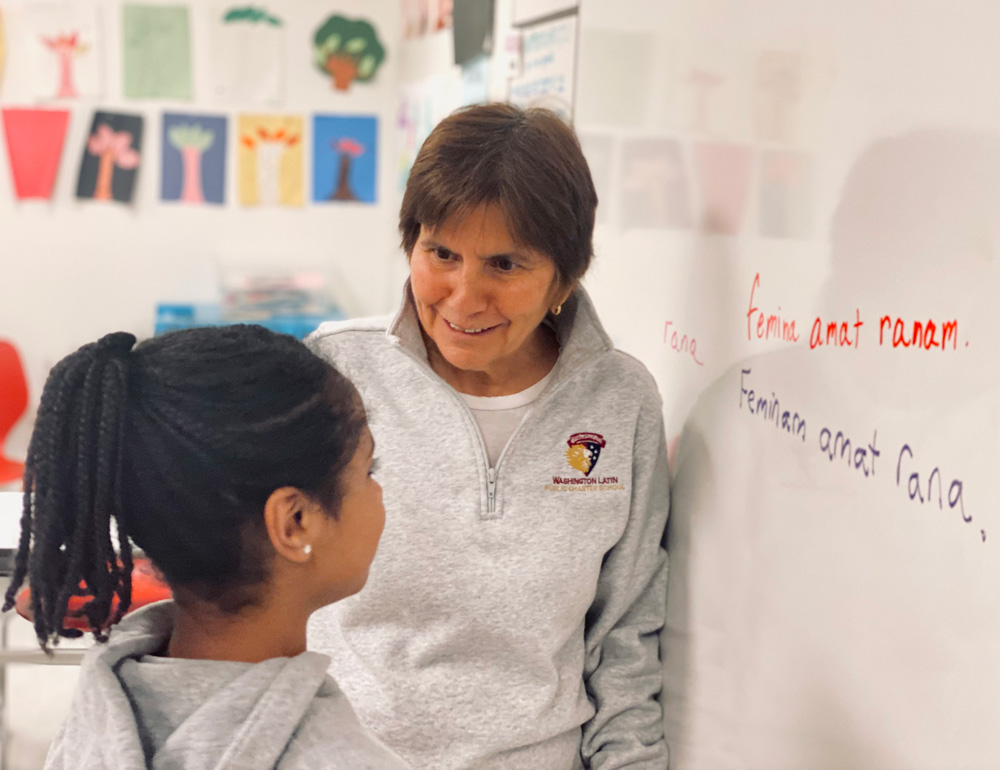

On a handheld whiteboard, Smith jots a word that perhaps 1 in 10,000 adults could define: “Aetiology,” the study of causes and origins. Not contenting herself with one stumper, she quickly adds more SAT material below it, this time written in Greek letters: “Logos.” Coaxing the kids to recite them with her, she wonders aloud what they could mean.

If the prompt is a bit advanced for 10-year-olds, no one seems fazed. In fact, through the rest of the 80-minute period, Smith’s students gamely follow along as she traipses through more of the antiquarian lexicon, sometimes gesturing toward the image of an early modern masterpiece that decorated the walls of the Vatican for over 500 years. The tutorial, part of the school’s foundational coursework for young pupils, is a concentrated dose of a pedagogy that Smith has spent much of her career refining.

Washington Latin’s approach to K–12 schooling comes from the somewhat esoteric world of classical education, a movement dedicated to reviving liberal arts instruction as it was understood by the men (and one woman) depicted in The School of Athens: Socrates, Aristotle, Diogenes, Pythagoras and Archimedes. After decades building schools and writing curricula in the parochial and homeschool sectors, its most ardent proponents can sound like evangelists for a long-abandoned faith, laying a heavy emphasis on dead languages and peppering their own speech with words like “quadrivium.”

But the leading minds in classical education are fixated by the future as much as the past. Pitching a humanistic alternative to both progressive and state-sponsored school reform efforts, established players like the southwestern Great Hearts network and Hillsdale College’s Barney Charter School Initiative are attracting more families and diversifying their offerings. With millions of students leaving traditional public schools since the beginning of the pandemic, classical education providers are attempting to step into the breach with not only a content-rich model, but also a worldview extending deep into the foundations of (another phrase that gets used frequently) Western civilization.

Those efforts have met with early, if somewhat controversial, success in states like Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis has welcomed the arrival of seven Hillsdale-affiliated charters and is reportedly weighing the adoption of a classically oriented college admissions test as an alternative to the SAT.

The question is whether the opportunity for growth can be seized, or if the movement’s internal differences, religious as well as political, are too cacophonous to allow for anything but niche appeal. Some within the field worry that “classical” might become a byword for “conservative,” particularly as a growing number of activists and families have grown leery of public schools’ teaching of subjects like race, gender and sexuality. Others believe that classical education can’t fully deliver on its potential without religion at its core.

A public charter, Washington Latin sits at the center of some of these debates. It is a deliberately small program, its roughly 900 students divided into average class sizes of 18 in middle school and 15 in high school. Unlike some of the better-known actors in the classical charter world, it hasn’t laid plans for exponential expansion in the coming years, and its leadership acknowledges that its attraction to families in the nation’s capital rests more with its demographic diversity and strong academics than its classical orientation.

At the same time, the school is growing. After a years-long negotiation with district officials, its second campus opened last fall in a provisional space about a mile south of Catholic University. Though a more permanent site has already been selected nearby, Smith teaches for the moment in a former warehouse with few windows. The longtime Washington Latin principal now serves as its head of classical education, shuttling between campuses to observe and occasionally lead seminars like this one, which moves from ancient mythology to medieval history and back.

Noting that Raphael lived and worked around 1500, roughly 2,000 years after his Hellenistic subjects passed from the scene, Smith asks the significance of the term “renaissance,” derived from the Latin word for birth. A 10-year-old named Alice thrusts her hand up.

“It means to be born again, but it’s not just talking about people,” she offered. “It’s talking about ideas or beliefs from the past being used again. It’s the rebirth of an era, into the modern day.”

‘We can’t get away from Plato and Aristotle’

The ascendance of classical education in the 2020s is itself a tale of rebirth.

What properly qualifies as “classical” instruction is somewhat contested, but the term generally refers to the educational strategies descended from the ancient civilizations of Greece and Rome. In those rigidly ordered societies, the honing of the mind was seen as a pursuit for the sons of prominent families. The masses — women, the poor, vast populations of slaves — received little or nothing in the way of formal schooling.

It was the teachers of antiquity who laid the foundations of Western thought: Socrates, sentenced to death for corrupting the youth of Athens; Plato, whose Republic provided the quintessential vision of justice for both man and the state; and Aristotle, tutor to Alexander the Great. In their explorations of the nature of existence and virtue, all three inspired not only the intellectual awakening of their own age, but also those of the early Christian period, the Middle Ages and the Enlightenment.

“If we live in the West, which we do, we can’t get away from Plato and Aristotle,” said Susan Wise Bauer, a publisher and homeschooling advocate who has written widely on theories of classical instruction.

With the development of mass education in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, some felt that cultural inheritance, and the pedagogy necessary to transmit it to future generations, were being abandoned.

In a 1947 essay, “The Lost Tools of Learning,” the British author Dorothy Sayers remarked on the paradox of widespread literacy being accompanied by the rise of propaganda and advertising, the seeming inability of the public to distinguish truth from misinformation, and what she identified as the chief failure of modern schooling: “Although we often succeed in teaching our pupils ‘subjects,’ we fail lamentably…in teaching them how to think.”

To reverse this confusion, she argued, educators needed to rediscover the educational program pioneered in the ancient world and ubiquitous in European schooling for a thousand years: the trivium, a three-part sequence of grammar, logic and rhetoric.

The trivium — along with the similarly dusty-sounding “quadrivium” of arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy — makes up what were historically known as the liberal arts, and form much of the substance of the revived classical education movement. To the thousands of families and teachers drawn to it, the antique origins of the liberal arts represent a sturdier basis of learning than the progression of newfangled interventions and orthodoxies that have emerged in recent decades.

“We’re starting to see, parents and educators alike, that we need to return to a better way of doing things,” said Kathleen O’Toole, the assistant provost for K–12 education at Michigan’s Hillsdale College, which has launched or partnered with dozens of schools around the United States. “We need to stop trying to innovate, stop trying to experiment when it comes to K–12; we think the answer lies in some sort of return.”

A lack of ‘core knowledge’

As in the 1940s and ‘50s, part of the dissatisfaction with mainstream public schooling arises from the perception that much of what is taught in classrooms lacks spark and rigor, leading to a disenchantment with learning and a devaluing of the arts and humanities.

The most obvious manifestation, critics say, can be seen in higher education, where federal data indicate that the number of degrees awarded in languages, literature, history, philosophy, and religion have plummeted in the last two decades. But even among younger students, disturbing signs are emerging. By their own admission, American kids are reading for pleasure at the lowest levels since the 1980s, and in an echo of Sayers’s warning, at least one study has shown that the vast majority of high schoolers have only a slipshod sense of media literacy.

Jeremy Wayne Tate is a classical education proponent and entrepreneur who founded the Classic Learning Test, an alternative to the SAT that has caught on with Christian classical universities and recently gained the attention of DeSantis in Florida. Despite mainstream American schooling’s overwhelming focus on the cultivation of skills for college and career, he argued, huge numbers of students graduate in a state of “educational neglect.”

“They spend 12 years and graduate without any serious core knowledge,” Tate said. “They don’t have knowledge of the great books and the classics, but they don’t have any vocational skills either. You almost want to say, ‘Do one of these things!’”

At Washington Latin, the aim is to combine a classical course of study with a grounding in and acceptance of the contemporary — or, as the institutional motto puts it, “a classical education for the modern world.”

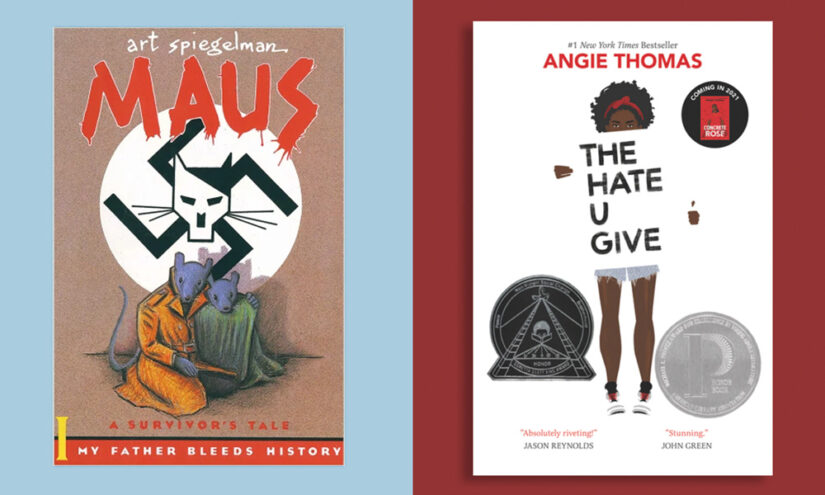

All students take at least three levels of Latin, with an additional option of Greek. But the school also requires credits in modern languages like French, Mandarin, and Arabic. Courses in robotics and computer science accompany robust helpings of world history and literature. The high school’s summer reading list highlights texts from a diverse array of authors past and present — including Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, both of which have drawn complaints from parents in other states.

Particularly for children in younger grades, the classical bent can veer more toward the conceptual. In an elementary math exercise, for example, students are asked to design a poster or comic strip illustrating fractions. At adjoining desks, 10-year-olds Justice and Maddy work on an eight-panel story of a group of friends dividing three cookies.

After only a few months attending their new school, which opened exclusively to fifth- and sixth-graders in September, they have largely adjusted to its structure and routines. Justice compares the experience to that of her last school, a local Montessori whose self-directed ethos emphasized “finding yourself and doing your own thing.”

“We learned a lot too, but we usually started drawing and doing funner” — she quickly corrects herself — “more fun things. So this is more of a straight education instead of just doing what you want, when you want. It’s a bit of a transition not being able to, like, crochet during the lesson.”

‘Explosive’ demand

Judging from local interest, Washington Latin’s approach and offerings are extremely popular. Since the school, like many charters, is oversubscribed, it runs a lottery to determine admissions; recent data from the school district show that nearly 1,100 students are currently on the waitlist for seats at its original middle school campus.

That partially reflects the school’s enviable academic results. On district-wide standardized tests last year, 58 percent of Washington Latin middle and high schoolers performed at or above grade level in English, compared with 30 percent of D.C. students overall. Forty-seven percent of its middle schoolers, and 29 percent of high schoolers, scored at or above grade level in math, compared with just 19 percent of Washingtonians in those grades.

But its strength in enrollment mirrors the rest of the classical education space, which has likewise seen what Tate of the Classical Learning Test called an “explosive” surge in demand in recent years.

Much of it has come in the parochial sector. According to the Association for Classical Christian Schools, an organization that offers training and accreditation to Protestant classical academies, its membership now stands at over 400 schools enrolling between 60,000 and 70,000 students; those figures appear to have leapt by as much as 50 percent over the last half-decade.

Catholic institutions are making their own strides. Since Chesterton Academy opened in Minnesota in 2008, the “joyfully Catholic, classical high school” has spawned 43 successors across the United States, Canada, Italy, and even Iraq. In the fall of 2021, the Archdiocese of Boston opened the Lumen Verum Academy — its first new Catholic school in a half-century — which features a classical curriculum and operates on a “blended learning” schedule.

But nowhere is the expansion of the classical footprint more noticeable, or more controversial, than in the charter sector. Great Hearts, which already operates over 30 charter schools across Arizona and Texas, will soon open new campuses in Louisiana and Florida and launch a national, online academy this fall. In a recently published interview with education commentator Rick Hess, CEO Jay Heiler announced plans to leverage Arizona’s Empowerment Scholarships Account program to launch “private schools with church communities” in that state.

The other major entity in classical charters is Hillsdale’s Barney Charter School Initiative, which made national waves in 2022 by applying to open three charters in Tennessee at the invitation of Republican Gov. Bill Lee. Hillsdale gained prominence during the Trump administration as a popular speaking venue for conservatives; its president, Larry Arnn, led President Trump’s commission to create a “patriotic” U.S. history curriculum as an alternative to the 1619 Project.

Though the partnership between Tennessee and the Barney Initiative was meant to eventually bring 50 Hillsdale-affiliated charters to the state, the proposal came under fire after Arnn was unwittingly recorded opining that public school teachers are trained “in the dumbest parts of the dumbest colleges in the country.”

Criticisms of the phonebook-sized “1776 Curriculum” added additional strain, with critics citing questionable ideological pronouncements embedded in its lessons (the Civil Rights Movement was “almost immediately turned into programs that ran counter to the lofty ideals of the Founders,” one passage read). With bipartisan detractors growing louder by the week, the initial charter proposals were withdrawn last fall.

By the middle of last year, suspicious progressives were increasingly associating classical education with the political Right. Notably, however, figures within the private wing of the movement have also expressed some skepticism of how the moral instruction of classical education could be applied in a charter school. David Goodwin, head of the Association of Classical Christian Schools, argued that true classical instruction “cannot exist without a transcendental.”

“My judgment is that Barney largely does that with the Constitution and the American Declaration — what they’re trying to do is use the Bible as maybe a supporting document for Americanism.”

O’Toole, who founded and led a classical charter in Texas before her stint at Hillsdale, said that while there were “fundamental questions about divinity…that we are not going to take up in a direct way” with students,” she preferred the charter environment to that of an independent school and didn’t “see it as a hindrance at all that we don’t talk about religion.”

Washington Latin’s Smith, a Christian, argued that the study of “timeless truths” doesn’t require sacred underpinnings; Socrates and Plato, to take obvious examples, were not Christian or even monotheistic, and their philosophical explorations have influenced secular as well as religious systems of thought.

“I get as close as I can to talking about schooling in a religious way without being religious, because it’s a public school,” she said. “But it’s holy work that we’re doing, and if you’re in the school, you’ll get a feeling of the transcendent — a feeling of inspiration.”

Fears of partisanship

The divides within the movement are a long way from becoming all-out fissures — in fact, most parents still aren’t aware of their existence.

But signs of its increasing prominence are stoking worries that, as with seemingly everything in American life, polarization will eventually discover classical education. Tate, a vocal cheerleader for school choice who has called classical schools a necessary corrective to what he views as the leftward drift of public schools, said he was “concerned” that partisanship might come to overwhelm their appeal.

“As a conservative, I don’t want to see this movement politically hijacked. But there are aspects of it that are threatening to the progressive establishment.”

Many in the national press got their first exposure to classical education in January, when DeSantis unveiled a controversial plan to shake up the leadership at the New College of Florida, viewed locally as one of the state’s most progressive universities. The administration’s hope, his chief of staff told the press, was to transform it into a classical institution akin to a “Hillsdale of the South.”

Wise Bauer, the homeschooling author, grouped DeSantis with other conservative actors aiming to “co-opt” the branding of classical education as a means of appealing to right-wing instincts of what should be taught and excluded from school curricula.

“What I see right now is this big battleground where some people — and I would put Ron DeSantis in this category — use ‘classical education’ without reference to the process, but only in reference to past thinkers who were white and European,” Bauer said.

For her own part, Smith contrasts the outlook of her school with those of more conservative classical Christian and public charter programs, which “tend to treat the modern world as a problem that needs solving.” The building in which she stands, Washington Latin’s newly opened Anna Julia Cooper Campus, takes its name from a pioneering African American educator and classicist who made her home in Washington, not Thebes or Athens.

“We don’t have the same attitude towards the time period that people have been born into,” she continues. “What we’re trying to do is bring the wisdom, the curriculum, and the pedagogical approach of the Socratic seminar to a public school audience.”

The school’s climate clearly differs from that of progressive icons like Montessori, but also from many of its famous counterparts in the charter sector. For the most part, students come and go as they please without falling into silent transitions through the hallways. During some class periods, they are allowed to sit in chairs or on the floor. Smith describes their freedom of movement as reflecting the liberal embrace of individual autonomy, even in the case of elementary schoolers.

As if to illustrate the point, several classrooms soon empty into a jumbled mass of pre-adolescent energy, breaking for a 20-minute interval between periods. About two dozen kids are soon sitting on the stairs of the building’s main foyer, chatting or playing quick rounds of chess.

Two friends, Alex and Nikolas, practice bringing out their knights on a linoleum board while entertaining the question of whether even reigning World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen could outplay a computer. Likely not, they conclude; in this realm, human genius has yielded to the heights of mechanical proficiency.

Soon after, finishing their own game, they scuttle back to their next encounter with the ages.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter