(The Conversation) — The existence and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. have been the topic of ongoing debate ever due to the fact his assassination on April 4, 1968.

Nowadays, those invoking King’s memory assortment from Black Lives Matters organizers and President Joe Biden to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Educators attempting to educate Black record get in touch with on his ideas, even as their opponents declare that classes about systemic racism go against King’s drive not to choose people today “by the coloration of their pores and skin.”

In an age of polarization, it is truly worth remembering that a person of the pillars of King’s philosophy was pluralism: the notion of a number of communities engaging a single yet another, acknowledging their dissimilarities and shared bonds, and striving to build what King called a “Beloved Neighborhood.”

As an African American philosopher who studies comparative faith, I am primarily interested in what part religious pluralism performed in King’s battle for civil legal rights in the United States of America and human liberation all over the earth.

A refrain of faiths

King’s worldview was deeply nurtured by his experiences in the Black Church, wherever the Bible’s tales of flexibility and oppression are central. The Ebook of Exodus, for illustration, tells the tale of Hebrew slaves in search of deliverance, and the message has been a repeated concept in Black hymns and preaching for centuries. In the E book of Amos, the prophet cries out, “Allow justice roll down like waters” – which is a line King famously quoted in his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Making off the perform of other revolutionary Black Christians, King embraced interfaith leadership. His mentor Howard Thurman, who founded the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, traveled to India to satisfy with activist Mahatma Gandhi, who was Hindu.

Gandhi’s technique to nonviolent protest was also influential for Mordecai Johnson, president of Howard College, whose sermon on the issue just after a excursion to India in 1949 profoundly shaped King’s spiritual philosophy.

The spiritual variety of King’s coalitions was evident in situations like the 1965 March on Selma, exactly where some individuals have been seriously overwhelmed by police on “Bloody Sunday.”

Marchers came from a chorus of faiths that provided priests and nuns, Episcopal seminarian, high-profile Unitarian Universalists like James Reeb, who was murdered times later on, as well as Jewish leaders like Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Civil legal rights marchers attend the memorial support for Unitarian Minister James Reeb, who was killed by segregationists during the Selma-Montgomery marches.

Flip Schulke Archives/Corbis Historic via Getty Photos

Complementing his Black Church upbringing, King was inspired by knowledge throughout continents and cultures, from the Greek classics and Gandhi to Buddhist leaders like Thich Nhat Hanh. Despite their differing dogmas, he hoped leaders from throughout the religious spectrum and people of no specific religion would sign up for initiatives to encourage financial and racial justice and stand against imperialism.

‘The good entire world house’

When King applied the phrase “pluralism,” he assumed that its ideal of belonging had each religious and racial connotations. For example, King praised the Supreme Court’s decision in Engel v. Vitale, which concluded that community educational institutions could not sponsor prayers, and which segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace opposed. “In a pluralistic society these kinds of as ours, who is to figure out what prayer shall be spoken, and by whom?” King mentioned in a 1965 interview.

More than a decade earlier, throughout his time at seminary, King had penned a paper exhibiting a keen awareness of Christianity’s connections with other faiths: “To focus on Christianity without the need of mentioning other religions would be like talking about the greatness of the Atlantic Ocean without having the slightest mention of the numerous tributaries that keep it flowing.”

George Maislen, still left, president of the United Synagogue of America, offers an award to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. alongside Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Bettmann through Getty Photographs

Other vivid imagery like “the terrific environment property” underscored how King interpreted all persons and all faiths as dwelling in an interconnected world wide web. Figuring out widespread themes in the discrimination versus Indian Dalits, the castes previously known as “untouchable,” and the plight of African Us citizens in the U.S., King surmised, “I am an untouchable.” He also saw parallels in between the African American battle for freedom and the operate of labor unions such as the National Farm Personnel Association.

“Injustice wherever is a threat to justice everywhere you go,” King insisted.

King then, nowadays, tomorrow

King preferred individuals to embody the highest varieties of their individual religion and morality. Faith at its most effective, he believed, promoted peace, knowledge, like and superior will. This is legitimate of “all of the great religions of the entire world,” he wrote in a statement for Redbook journal.

Individuals ended up the forms of ethics King hoped to satisfy in his personal Christian ministry, as is clear in his wishes for what may possibly be explained at his individual funeral.

“I’d like any person to point out that working day that Martin Luther King Jr. attempted to give his everyday living serving other people,” he claimed. “I’d like for anyone to say that working day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried out to adore somebody. … I want you to say that I tried to appreciate and serve humanity.”

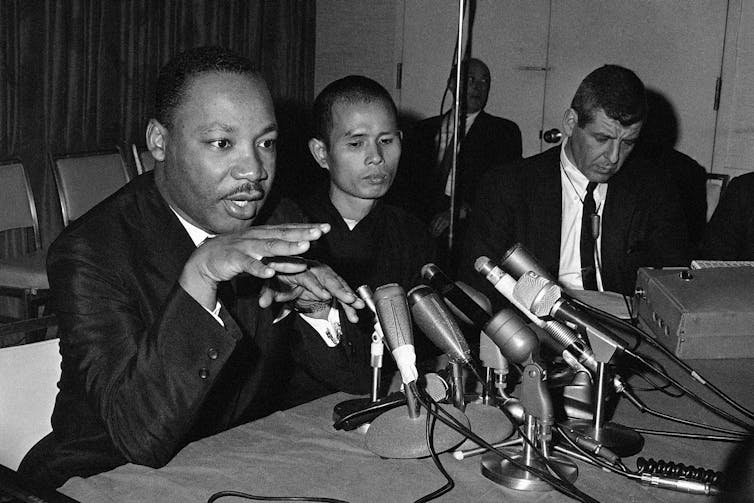

Martin Luther King Jr., still left, speaks through a Chicago information convention with the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh in May 1966.

AP Photo/Edward Kitch

Still King’s intention of a planet without starvation, war and racism remains unrealized. Poverty persists. War continues. Black people’s safety is nevertheless imperiled.

Resolving latest social and political crises in The usa could involve the real integration and power-sharing that King’s radical vision demanded.

Even so, the debate about King’s pluralist legacy is not only about him, but also about us. How do we want to be remembered? What earth are we leaving potential generations?

(Roy Whitaker is an affiliate professor of Black religions and American spiritual range at San Diego Condition College. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those people of Religion Information Support.)